|

This

feature appears in Auto Italia - Issue 119 |

|

|

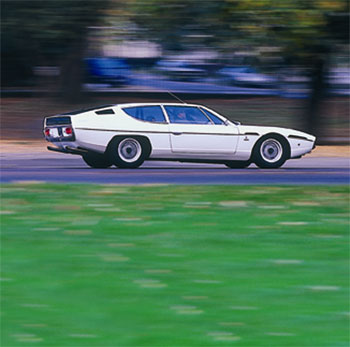

Like a spaceship parked outside Tescos, the sight of a

Lamborghini Espada fighting its way through West London is

somewhat surreal. While the van and taxi traffic edges its

way forward in ever decreasing circles, the big V12 creates

a forcefield of hydrocarbons around itself with each new

blip of the throttle. Pedestrians are inadvertently

asphyxiated as they cannot help but stare with open mouths

while local radio stations are preparing news items based on

sightings of a UFO on the Westway.

Well, it seems almost as long and wide

and certainly has some incredible flat surfaces but even the

Battlestar Galactica didn’t sound as meaty as this. Compared

with the 12-cylinder Ferraris of the same period, the

Lamborghini engine seems much more civilised with far less

chatter from chains and valve gear. It chooses instead to

use the exhaust system to project its voice, ranging from a

deep menacing throb at idle, through a kind of American V8

roar when the throttles are opened and building to an

Italian-only spine-chilling howl at the top end. It’s

intoxicating stuff, as our audience found out, but it

probably says as much for superior soundproofing and the

aforementioned exhaust acoustics from installation in the

Espada than any inherent civilisation of the motor – ask a

Miura owner if his engine sounds similarly sophisticated!

But of course, it is easy to forget when

you look at the outrageous exterior that the Espada was

supposed to be a sensible four-seater Grand Tourer – indeed,

the current owner of this car ‘sold’ it to his other half as

such when the children arrived (a feat worthy of respect

from half the population). The intention in its day was for

it to complement the more overtly sporting cars in the range

and also to maintain the momentum that Ferruccio

Lamborghini’s new company had gained.

By 1966, while Lamborghini cars had

already established themselves on the domestic market as

credible alternatives to Ferrari or Maserati, it would be

the presentation that year of the Miura that would really

launch the company worldwide. Nobody could have predicted

the enormous impact of this, the first mid-engined supercar,

but it put Lamborghini under pressure for the first time.

How do you follow that?

Lamborghini answered the question by

commissioning a concept car from Bertone, known as the

Marzal, and at the Geneva Salon almost exactly 12 months

after the Miura had changed the world forever, the Marzal

hoped to similarly challenge the established order. With its

enormous glazed gull-wing doors, pearlescent white paint (a

shade adopted even for the interior leatherwork) and an

obsession with hexagonal shapes which spread from the rear

bumper to the dashboard and everywhere in between, we could

easily dismiss it today as a piece of naïve kitsch, like a

set from Barbarella, but at the time LJK Setright said of

the Marzal that it was ‘perhaps the most extravagant piece

of virtuoso styling to have come out of Europe since the

War’.

The chief designer at Bertone at the time

was the now legendary Marcello Gandini, who in a recent

interview admitted that he preferred the overall title of

designer than that of stylist (for which he is probably best

known). For him, the real satisfaction has always come from

the engineering creativity as much as the pure aesthetics

and it shows in the Marzal. By taking an elongated Miura

chassis and half a Miura engine mounted behind the rear axle

line, the Marzal was able to seat four adults in comfort,

with easy access through the aforementioned gull-wing doors.

By-products of this were an incredibly low and wide frontal

area, a distinctive beltline and a huge glasshouse. Visitors

to Geneva may have been dazzled by the ‘space-age’ shapes

and colours but the real evolution was behind the façade.

As a concept, Marzal did fulfil its role

in foretelling the future but it did not work properly as a

car. The Miura chassis was not rigid enough when elongated,

the six-cylinder engine was woefully underpowered and the

suspension did not have sufficient travel in the low front

wheel arches. The motor-show-going public would have to wait

another year for that.

During the interim months, Gandini and

his team, working closely with Giampaolo Dallara at

Lamborghini, developed the Marzal concept into a prototype

for the Espada. The Miura frame was rejected in favour of a

new sheet steel semi-monocoque with integral tubular chassis

members and the already established running gear of the

400GT was fitted. This meant that the engine moved from the

back to the front and re-gained its full compliment of 12

cylinders. Compromise had to be made in terms of the height

of the frontal area but the engineers were helped by the

fact that the Lamborghini V12 had always been able to use

sidedraught carburettors instead of the more usual

downdraught type for V engines. From its inception, the

Giotto Bizzarrini-designed engine had featured inlet ports

set in between the inlet and exhaust camshafts on each bank

of cylinders rather than on the inward facing side of each

head. The manifold naturally curled outwards to

horizontal carburettors, decreasing the height of the engine

by probably 10cm over contemporary Maserati or Ferrari V

engines. It was a typical Bizzarrini touch from an engineer

who appreciated as much the aerodynamic and gravitational

dynamics of a ‘low’ engine as the gas-flow characteristics

of such a design.

The Espada prototype retained an overall

shape reminiscent of the Marzal, including tremendously

ugly, over-size gull-wing doors, which ate into the roof

space like those of a Ford GT40.

|

|

|

The only other true four-seater

GT car on offer from an Italian manufacturer at the

time was the majestic Maserati Quattroporte but, in

comparison, the Espada looked as though it was from

a different planet. |

|

|

|

|

|

This particular example may confuse the anoraks as,

although it is a Series 3, it has the earlier Series

2 wheels with knock-off spinners. |

|

|

|

Thanks go to the owner, Sean Gorvy, as well as to

Lamborghini expert Colin Clarke (also a previous

owner of this car) and to Rob Muller for his

location advice. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Like a spaceship parked outside

Tescos, the sight of a Lamborghini Espada fighting

its way through West London is somewhat surreal. |

|

|

|

Production commenced immediately

after Geneva in March 1968, and 186 cars were built

between then and November 1969 when the engine

received a 25bhp upgrade to 350bhp. At the same

time, the dashboard and interior were re-designed,

constituting the introduction of the Series 2

version which lasted for 575 units and until

November 1972, when the final dashboard and a change

of wheel design among other details signalled the

arrival of the third and last series. |

|

|

|

|

|

Compared with the 12-cylinder

Ferraris of the same period, the Lamborghini engine

seems much more civilised with far less chatter from

chains and valve gear. It chooses instead to use the

exhaust system to project its voice, ranging from a

deep menacing throb at idle, through a kind of

American V8 roar when the throttles are opened and

building to an Italian-only spine-chilling howl at

the top end. |

|

|

|

|

|

At the time LJK Setright said of

the Marzal prototype that it was 'perhaps the most

extravagant piece of virtuoso styling to have come

out of Europe since the War'. |

|

|

|

|

Thankfully, at the end of the day, the design team gave up

on an obsession with ease of rear seat entry and the final

prototype, with conventional doors and gold metal-flake

paint, was presented at Geneva in March 1968. It says much

for Gandini’s inherent talent and the greater simplicity of

the era that even after this distillation process the result

was still outrageous to look at from any angle. It was

particularly in the use of glass that the Espada broke new

ground. A larger glazed area was becoming more common but

rarely had the rear windscreen been used without a frame as

a tailgate, or the rear panel been glazed to increase

rearward vision. Even the rear quarter windows were enlarged

to the maximum possible size and hinged uniquely from the

top rather than the leading edge. The low beltline was

actually higher than that of the Marzal but still a striking

design feature complete with integrated slats in the bonnet

to reduce engine bay temperatures.

Nothing that had gone before had ever

looked like this. The only other true four-seater GT car on

offer from an Italian manufacturer at the time was the

majestic Maserati Quattroporte but, in comparison, the

Espada looked as though it was from a different planet.

Production commenced immediately after Geneva in March 1968,

and 186 cars were built between then and November 1969 when

the engine received a 25bhp upgrade to 350bhp. At the same

time, the dashboard and interior were re-designed,

constituting the introduction of the Series 2 version which

lasted for 575 units and until November 1972, when the final

dashboard and a change of wheel design among other details

signalled the arrival of the third and last series. 456 of

the last series cars were built up to the end of 1978 when

production was curtailed as Lamborghini entered a period of

receivership, guilty as were so many of confusing the market

with too many models, costing too much to build. Hence, when

the oil crisis began, they could not contract fast enough to

survive.

I was beginning to wonder about our own

personal oil crisis as we squeezed through the traffic once

more en route to Hyde Park. While the water temperature had

been refreshingly stable for an Italian supercar, the

prolonged idling was causing a little plug-fouling. Soon,

however, a couple of runs on the quiet park roads allowed a

little illegal throat clearing and all was well. In fact,

for such a space-rocket, the Espada had demonstrated a

surprisingly benign temperament. The pedals were heavy by

2006 standards, especially the throttle with its 12 separate

butterflies to open, but the power-assisted ZF box (an

option from Series 2 onwards) made light work of the

steering. The driving position was good, the ride compliant

from those chunky 70 profile tyres and the advantage of all

that glass was real confidence when placing the car on the

road. Contemporary road testers always concluded that what

was a large car shrank around them‚ and I think this was the

real reason. One could not hustle a Miura or a Countach in

such a cool-handed way in traffic. And when the opportunity

did present itself, the acceleration to light-speed was

always available, in any gear, at any time.

I think it was Marcello Gandini’s great

rival Giugiaro who said that anyone could design a supercar

but that the real talent lay in the greater discipline of

designing a practical family car. If so, then he must have

nurtured a certain professional jealousy over the Espada. It

was an outrageous piece of visual design, a perfect

complement to the Miura and then the Countach and yet all

the time a practical, easy-to-drive Grand Tourer with space

for family and luggage. It really was the spaceship you

could take to the supermarket.

Story by Andy

Heywood / Photography by Michael Ward

|

|

This feature appears in Auto Italia, Issue 119, May-June 2006. Highlights of

this month's issue of the world's leading Italian car magazine, which is now on sale, includes road tests of the

new Alfa Romeo Brera and Maserati Quattroporte GT; long-distance journey with the Premier

Padmini, Abarth Simca 1300 - the French

connection; and fun at the seaside with the Ferrari F430

Spider.

Call +44 (0) 1858 438817 for back issues and subscriptions. |

|

|

website:

www.auto-italia.co.uk |

|

|

![]()

![]()