|

This feature appears in Auto Italia - Issue 117 |

|

|

Somewhere in the

Land Of The Rising Sun there’s a piece of my heart. It’s a

blood-red wedge, surgically removed nearly 12 years ago

(it’s called a lottadoshtomy); but I still get the

occasional twinge of discomfort. The odd tooth, some hair,

countless pickled brain cells – they’re all gone and

forgotten. But a Stratos is like backache: once you’ve had

it, it’s with you forever. So, the call from His Wardship

offering me not one, but two of the little monsters to play

with, one of them a pukkah Group 4 example, was like that

first fag after a long-haul flight, you suddenly realise

how much you’ve missed it.

And talk of

addiction brings me neatly to Christian Hrabalek – a man

with no bad habits, I should add (that I know

of, anyway), but one in thrall to chronic Stratosphilia. Not

content with owning seven of them (it was 11 once…), he has

now masterminded the inspired 2005 Fenomenon

‘re-interpretation’ – you saw it here first – and signs of

remission are hard to detect. This Pirelli car is his, as

was the red stradale until he sold it to Gordon

McCullough three or four years ago. The cars cohabit not far

from Goodwood, allowing me to re-Stratify myself in the road

car on the way there, before blowing my mind (and the

circuit’s three ‘drive-by’ microphones) in the Gp4, both on

the track and on the way home.

The Road Car

(chassis no 1778)

This mint

machine was born on September 17th 1974, destined for the

German market, and represents the Stratos in its purest form

– Gandini’s sublime shape unspoil(er)ed by any bolt-on

addenda. The optional wings have always polarised opinion

aesthetically, but they work – Gordon says his car feels

decidedly ‘wobbly’ at 190km/h…Only the competition-pattern

15-inch Campagnolo wheels are non-standard, and next to the

fully kitted-out rally car (its senior by 19 days) it looks

almost effete. Mind you, so does Darth Vader. With its

bloated rear arches and massive P7s, its spoilers, roof air

vent and auxiliary light pod, the Gp4 looks downright scary.

And sounds it.

Chris takes it to Goodwood, leading a four-car convoy, and

the sublimely outrageous noise assaults my eardrums three

cars back where, driving the stradale, I’m

already wallowing in a tsunami of memories – from the

corkscrew-contortions needed to climb aboard to the

familiar, skew-whiff, just-left-of-centre driving position.

The non-standard Bordigari competition seat has a hard

lateral ridge under the thighs and could do with a longer

squab, but otherwise it’s just like coming home.

Ahead, the

swoopingly-curved ‘dash’ and seven-dial binnacle butt up to

a screen which is a geometrically perfect, constant-radius

cylindrical section (to minimize distortion). Combined with

the wonderfully slender A-posts (impossible nowadays,

sadly), it affords a view for’ard as panoramic as that aft

is pitiful. The re-acquaintance is swift, lines of

communication soon re-established. Your relationship with

that fabulous V6 is more intimate in a Stratos than in any

Dino, its distinctive, restless sound fluctuating wildly in

pitch and intensity in response to the throttle. Eager to

confront the 7500 red line, it has great flexibility lower

down, too, optimised by the sub-tonne weight.

Here again is

that light, ultra-precise steering that redefines

‘feedback’, the chunky gearchange and the rather

dead-feeling, but ultimately powerful, brakes. The

suspension is as alive as ever, the usual muffled clonks and

bangs reminding you that this is no all-mouth-and-trousers

poseur. But this one rides beautifully, too – always a sure

sign of a well set-up Stratos, with the right blend of

compliance and stiffness.

Tolstoyan

quantities of verbiage have been written about the Stratos’s

‘tricky’ handling, and mastering the range and degree of

adjustability built into the suspension requires skill and

experience. When a Stratos is good, it is very very good;

but when it is bad… In a nutshell, it’s about getting enough

bite at the front end to hold its own against stupendous

grip and traction from the back (weight distribution is

roughly 40/60% front/rear). Power understeer of cosmic

proportions is common – we’re talking

exiting-roundabouts-via-the-grass-verge stuff. Conversely,

with a wheelbase barely longer than its track, a Stratos can

react with alarming alacrity to ham-footed power reversals –

it’s the only car I’ve ever spun on a public road. But not this

one. Like the Pirelli car, it was prepared by Luigi Foradini.

Between 1970 and 1980, Biella-based ‘MFS’ – Foradini,

sandwiched by (Claudio) Maglioli and (Piero) Spriano –

worked wonders with Strati, both for the factory and, later,

French privateers Chardonnet. The ‘F’ touch is clearly still

intact, for here is virtual Stratos perfection.

Chris holds us

to a stately pace, so I hang back periodically, trying to

goad the car into misbehaviour. I try all the tricks,

loutishly manhandling both throttle and wheel with all the

subtlety of a Little Britain sketch. But both ends work

together beautifully, the sharp steering responses

unimpaired by any waywardness. The front really bites on

turn-in and, once settled into a bend, it’s at the back you

feel the lateral loading. But the modestly-proportioned

Michelin TB15 road/race tyres – the sine qua non

of ’70s/’80s club-racing, now being re-manufactured – have

grip enough to keep the tail in line. They look pleasingly

similar to the original Pirelli CN36s, too – but won’t last

as long.

There’s only the

one roundabout to negotiate on our short journey but it’s

dauntingly tight, and I hang back again. It demands fast,

accurate directional changes, and that’s just what you get –

we’re through in a flash, leaving a virgin verge. Never was

the hoary old ‘go-kart’ analogy more appropriate. And never, in my

experience, was a road Stratos better set up. Appetite

wetted, I’m ready for the rude version…

The Group 4 Car

(chassis no 1723)

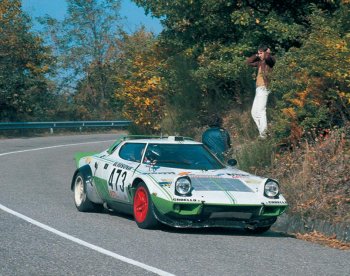

Stratoses wore

Pirelli colours only in 1978, their last ‘official’ season,

when Fiat itself came out to play with the 131 Mirafiori.

|

|

|

Chris Hrabalek’s car, originally also a red stradale, began its

competitive career with the Grifone team (painted red with a

white roof), had a spell with The Jolly Club (in a white and

lime green ensemble) and thereafter appeared regularly in

Italian national events crewed by such stalwart journeymen

as Cola, Pons and Alberti (second in the 1979 Rally

Autodromo Monza and eighth in 1980’s Giro D’Italia

stand out). |

|

|

|

|

|

When Chris Hrabalek bought the Stratos, in 1991, it

wore Alitalia livery

and was in need of total restoration. Foradini duly obliged,

re-building it to 1978 works specification. Both four-valve

per-cylinder engines and straight-cut gearboxes were

outlawed that year, so it features the latest-evolution

two-valve engine and a gearbox with notional synchromesh –

plus bigger Lockheed brakes and, of course, Pirelli colours. |

|

|

|

|

|

This mint

machine was born on September 17th 1974, and which was destined for the

German market, represents the Lancia Stratos in its purest form

– Gandini’s sublime shape unspoil(er)ed by any

bolt-on addenda. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

This Pirelli Stratos is Chris Hrabalek's, as was the

red stradale until he sold it to Gordon

McCullough three or four years ago. The cars cohabit

not far from Goodwood. |

|

|

|

|

|

'Fun' doesn’t come close to describing a Stratos.

It’s got it, it flaunts it, and Chris knows as well

as anyone what a tough act his Fenomenon has

to follow. In any Stratos, every journey’s a special stage –

very special. |

|

|

|

The Stratos’s enforced

retirement was at best premature, at worst plain daft; but

at least the bean-counters had to suffer the embarrassment

of watching the old girl accumulate yet more silverware for

several years to come – much of it courtesy of Chardonnet…

and MFS. |

|

|

|

|

They judged their repmobile to have far more profit-making

potential than the elitist Lancia – and nicked its trademark

Alitalia livery for good measure. The Stratos’s enforced

retirement was at best premature, at worst plain daft; but

at least the bean-counters had to suffer the embarrassment

of watching the old girl accumulate yet more silverware for

several years to come – much of it courtesy of Chardonnet…

and MFS.

Chris’s car,

originally also a red stradale, began its

competitive career with the Grifone team (painted red with a

white roof), had a spell with The Jolly Club (in a white and

lime green ensemble) and thereafter appeared regularly in

Italian national events crewed by such stalwart journeymen

as Cola, Pons and Alberti (second in the 1979 Rally

Autodromo Monza and eighth in 1980’s Giro D’Italia stand

out). When Chris bought it, in 1991, it wore Alitalia livery

and was in need of total restoration. Foradini duly obliged,

re-building it to 1978 works specification. Both four-valve

per-cylinder engines and straight-cut gearboxes were

outlawed that year, so it features the latest-evolution

two-valve engine and a gearbox with notional synchromesh –

plus bigger Lockheed brakes and, of course, Pirelli colours.

Corkscrewing

into this beastie takes you into a very different

environment. Gone is the prominent binnacle, in its place a

conventional full-width dash, chock-a-block with stuff, all

with its original Italian labelling. I lost count of the

light switches (a navigator’s nightmare), there’s a

pull-knob for ignition, a rubber starter button and two fuel

pump switches (left and right tanks) – all sharing a

wonderfully precision-engineered feel. In the centre, a

large knurled aluminium wheel controls brake bias, while two

Halda Tripmasters confront the co-driver.

At his feet, an

alloy footrest matches the driver’s perfectly placed pedals,

and both have grippy Sparco seats best suited to bums a

trifle narrower than mine. Like the road car’s Bordigari, it

won’t distract me for long. Rear visibility is even worse

here though, the interior mirror filled by the monstrous

glassfibre airbox which obscures both engine and outside

world alike.

After its aural

bombardment of West Sussex I didn’t rate our chances of

getting it onto this most noise-conscious of circuits. But

Chris was well prepared, producing two exhaust mufflers the

size of buckets and sailing through the ‘static’ test.

However, the three circuit mics aren’t as easily fooled, and

its first expedition, with Gordon at the helm, earned it a

red flag (er, black, surely?…).

No problem, we

were told – just back off at those three strategic points

and you’ll be okay. No problem in a familiar, ‘ordinary’ car

perhaps, but first time out in a Group 4 Stratos it does

nothing for your concentration and flow. I’m ready for

anything as I ease out of the pitlane, Chris beside me, but

the surprises are all nice. It’s set up as a

‘tarmac’ car, requiring grip and precision, and of the

pendulous back end – de rigueur for loose surfaces – there’s

little sign. With so short a wheelbase, the massive rear P7s

have a big part to play here (the smaller-than-standard

fronts look almost lost by comparison) and, although well

stricken in years, they perform impressively.

Being ‘live on

air’ makes for some jerky old laps, though. Blat through

Madgwick (at its skittiest here) – lift for the mic; flat

through Fordwater (beautifully stable), composed and agile

through St Mary’s – lift for the mic; boot the tail hard to

tighten the exit from Lavant, then flat down the straight…

and some respite. Here, the ultra-low gearing (there are

numerous alternatives) is obvious. Around 120mph is your lot

– there’s no speedometer – and I’m clean out of revs by

Woodcote. It’s as sharp as a knife into the chicane,

inviting a bootful out on to the straight… er, lift for the

mic.

Frustrating, all

this, but the message came over loud and clear. You have to

be masterful with this car; give it large – plenty of

everything – and it delivers. Rock solid with the power on,

surprisingly well-mannered on lift-off, it was far nicer

than I’d expected on the circuit. The steering is usefully

higher-geared than the road car’s, the clutch surprisingly

light and progressive, the brakes unsurprisingly

heavy but effective. The gearbox’s regulation-compliant

‘synchromesh’ (nudge, wink) is largely illusory in practice,

and the shorter-than-standard lever throw requires a firm

but deft hand (and probably no clutch, though I thought

better of trying it).

Then there’s

that engine – still flexible, but demonic above about

4500rpm. Its 280bhp matches a 24-valve motor’s output in

1977 (such is progress) and it’s clearly quicker than the

road car – although on the wide-open spaces of Goodwood it

didn’t feel all that fast by today’s standards. On a narrow

forest dirt track, in the dark, it’d be a different story…

And on the road,

where it’s a bit of a fish-out-of-water, its uncompromising

competition credentials are all-too apparent. The engine is

docile enough, but the very un-muffled crash-bang-wallop

from the all-steel suspension (gone is the road cars’ rubber

insulation) and awkward low-speed gearchanges would soon sap

your energy. And it was on the way home that I experienced

the scariest moment of the day – pulling out of a petrol

station. Rear three-quarter visibility was not a priority.

But, road and

track, it was great to be back. ‘Fun’ doesn’t come close to

describing a Stratos. It’s got it, it flaunts it, and Chris

knows as well as anyone what a tough act his Fenomenon has

to follow. In any Stratos, every journey’s a special stage –

very special.

Test by Simon Park /

Photography by Michael Ward

|

|

This feature appears in Auto Italia, Issue 117. Highlights of

this month's issue of the world's leading Italian car magazine, which is now on sale, include road tests of the new

Alfa 159 and

Fiat Grande Punto Sporting 1.9 JTD,

as well as features on Batman's Lamborghini

Murciélago and a pre-war Alfa Romeo 1750SS.

Call +44 (0) 1858 438817 for back issues subscriptions. |

|

|

website:

www.auto-italia.co.uk |

|

|

![]()

![]()