|

No other product

in history has taken humiliation, destruction and poverty

and made them the stuff of dreams. The Vespa, the original

and best Italian motorino(scooter) has just turned 60, and

despite 20,000 mechanical changes, 120 different models and

total sales of more than 16 million, it is still

recognisably the same machine as the one that made its debut

in April 1946.

Inside, though,

everything has changed: the old two-stroke engine, as

responsive and peppy as it was noisy and polluting, has

given way to a clean, quiet four stroke; the transmission is

automatic. But the look is essentially unchanged. For one

new model, the makers are even putting the headlamp back on

the mudguard, as it was on the original. They can't tamper

with the look too much - they can only tease and titivate

it, adding leather seats, fiddling with the shape of the

handlebars - because the Vespa is much more than just

another two-wheeler: In one clean, sleek piece of machinery

it says Italy, with all the sweet connotations that word has

acquired: sunshine, speed, voluptuous olive-skinned women,

casually impeccable men. It says Gregory Peck and Audrey

Hepburn, breezing through the city in Roman Holiday. More

than the Mini, the Jaguar, the Aston Martin or the Ferrari,

the Vespa is the ultimate cool machine.

But is also, in

much of the world, the poor man's saloon car, the simplest

and cheapest family vehicle. What the sit-up-and-beg bicycle

was in Mao's China, the Vespa was, and to a large degree

remains, in the teeming cities of India, carrying husband,

wife, nursing baby, two children and luggage on family

excursions. When the Vespa came into being, Italy, too, was

a poor country. Enrico Piaggio, the son of the founder of

the company of the same name, was an aeroplane builder. His

designer, Corradino D'Ascanio, was an aeronautical designer

who built the first modern helicopter. But in the spring of

1946, ravaged by war and invasion, this country did not need

more planes and helicopters. Italy needed to get out of the

rubble of its bombed cities and on to the potholed road. The

country had no money and no work, no place to go and nothing

to do when it got there, and its whole future to invent from

scratch. The Vespa was the product of desperation, and the

answer to desperation.

One reason it

did so well, from the day it launched, was that it was the

ultimate anti-motorcycle motorcycle. What makes motorbikes

irresistible to the minority of the population that finds

them so is precisely what makes them obnoxious to everybody

else. They are intimidating, noisy and dangerous looking.

They go much too fast. You have to lie almost flat to ride

them, wearing heavy protective clothing, and you look as if

you are going to die. It is almost impossible to ride them

and not get dirty. Piaggio's good fortune was that Corradino

D'Ascanio belonged to that segment of the population that

really hates motorbikes. So he produced a two-wheeler

radically different from any that had been previously

thought of, as if the classic motorcycle had never existed.

Yet if Piaggio

had given the nod to D'Ascanio's last prototype but one, the

whole project might have sunk without trace - and Italy's

reputation for elegance, style, sexiness etc with it.

Because that prototype, the MP5, stank. It was nicknamed "Paperino",

the Italian for Donald Duck, because of its ugliness. The

fundamental ideas of the scooter were already present, the

notion of hiding the engine and protecting the rider behind

a curving sweep of steel that culminates in the handlebars.

But a crucial final step had yet to be taken: the engine's

bulk was still throbbing between the rider's splayed legs.

Piaggio told D'Ascanio to have another try.

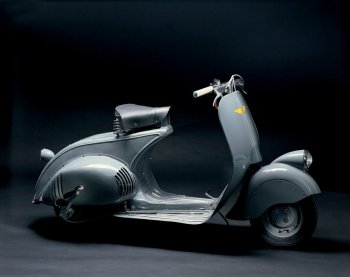

With the MP6,

the breakthrough was achieved. D'Ascanio slices out the

engine, as if with a sweep of a butter knife, and banishes

it to the hubs of the back wheel where it sits like a

bulbous growth either side of the chassis. Nothing but air

separates the seat and the handlebars, and the rider can

place his or her feet on the spacious, empty platform with

knees together as if sitting at the table of a cafe eating a

gelato.

|

|

|

The

Vespa MP5 was nicknamed "Paperino",

the Italian for Donald Duck, because of its ugliness. The

fundamental ideas of the scooter were already present, the

notion of hiding the engine and protecting the rider behind

a curving sweep of steel that culminates in the handlebars.

But a crucial final step had yet to be taken: the engine's

bulk was still throbbing between the rider's splayed legs. |

|

|

|

The Vespa's extraordinary

longevity - it has far

outstripped other cult motoring

object such as the Mini and the

Beetle - owes much to its

revolutionary design; but also

to Italian cities, many of which

are impossible to negotiate by

any other means. |

|

|

|

Piaggio have celebrated

the 60th anniversary of the Vespa scooter by

introducing the special GT-60 model. |

|

|

|

|

No other product

in history has taken humiliation, destruction and poverty

and made them the stuff of dreams. The Vespa, the original

and best Italian motorino(scooter) has just turned 60, and

despite 20,000 mechanical changes, 120 different models and

total sales of more than 16 million, it is still

recognisably the same machine as the one that made its debut

in April 1946. |

|

|

|

Piaggio took one look at the MP6, with its bulbous

yet aerodynamically curving engine housing and

exclaimed: "Sembra una vespa!" -

"It looks like a wasp!" The name

stuck, and was soon being

applied to the infernal whining

of the machine's two-stroke

engine as the swarms took over

Italy's cobbled lanes. |

|

|

Piaggio took one look at that

revolutionary design, with the

bulbous yet aerodynamically

curving engine housing and

exclaimed: "Sembra una vespa!" -

"It looks like a wasp!" The name

stuck, and was soon being

applied to the infernal whining

of the machine's two-stroke

engine as the swarms took over

Italy's cobbled lanes.

The 1950s were the beginning of

the heyday of the Vespa: one

million scooters were produced

in its first decade, and

factories opened in Britain,

Germany, France, Belgium, Spain,

Indonesia and India as well as

Italy.

Italy's transformation from a

picturesque but rather

ridiculous place, the home of

spaghetti and Fascism, to the

epitome of Mediterranean chic,

was well under way. It was

incarnated in figures such as

Gianni Agnelli, the elegant boss

of Fiat, who had A-list friends

across the world; in products

such as the Olivetti typewriter

and modern Italian furniture; in

the burgeoning film industry and

its extraordinary directors,

Fellini, Pasolini, Visconti. But

nothing captured the spirit of

that transformation better than

the Vespa.

It epitomised the way that - in

the teeth of American cultural

hegemony and although profoundly

influenced by America - Italy

managed to plot its own postwar

course, to create its own icons

of style. American cars sprouted

absurd fins and ballooned ever

larger. Yet no American in a

Chevy ever looked cooler than

Gregory Peck squiring his

princess past the Coliseum on

the Vespa. That was 1953, and

sales of the machine went

through the roof. And American

celebrities came flocking.

Marlon Brando, Ben Hur director

William Wyler, Charlton Heston

and John Wayne were among the

Americans who succumbed.

It was on the coat tails of

Roman Holiday that the Vespa

charisma crossed the Channel

and, in the mid-60s, became the

defining element in the Bank

Holiday wars between Mods and

Rockers. The Rockers, like the

Hells Angels they anticipated,

were greasy, dirty and hairy;

obviously trouble. The Mods were

more ambiguous; nicely turned

out in their Fred Perry sports

shirts and tight-fitting,

three-button, Italian-style

suits, sharp hair cuts and these

domesticated Italian

two-wheelers. But they were no

pushovers. They listened to ska

and soul music, the Action and

the Who; they took pep pills and

fought the Rockers on the sands

of Margate and Brighton with

chains and flicknives. They did

what no Italian would have

thought of and loaded their

Vespas with mirrors and

redundant waving antennas. With

Mafia chic somewhere in the mix,

the Mods reinvented the Vespa as

a war machine. They took it as

far as it would go. But they

couldn't kill it off.

Mods morphed into skinheads and

some of them still rode

scooters, but the Vespa on the

Italian cobbles - with stucco

and marble, wisteria and

umbrella pines in the background

- sailed on regardless.

The Eighties was the most

difficult decade for the Vespa,

because it signalled the arrival

of the Japanese. But thanks to a

mixture of protectionism and

patriotism, the Vespa did not

suffer the fate of Britain's

bike brands. Italy's roads today

are full of Yamahas, Hondas and

Suzukis, but the Vespas hold

their own: Piaggio, the company,

has refused to concede the

fight, bringing in supercharged

models while keeping the retro

market fully supplied. After

being banned from the US in the

1980s because the dirty

two-stroke engines failed to

meet emission standards, it has

returned with cleaner

four-stroke models.

Further developments are in the

offing. Piaggio tested a

zero-emission,

hydrogen-fuel-cell scooter this

year. The company's president,

Roberto Colaninno, said "On 11

May, at Campidoglio in Rome, we

will present Vespa with a

brilliant heir. We are talking

about a real revolution." Rumour

has it that Piaggio will unveil

the first Vespa three-wheeler.

The Vespa's extraordinary

longevity - it has far

outstripped other cult motoring

object such as the Mini and the

Beetle - owes much to its

revolutionary design; but also

to Italian cities, many of which

are impossible to negotiate by

any other means. There is

nowhere to park a car, even if

one has the patience to sit out

the interminable snarl-ups. In

ancient cities such as Rome, the

building of new subway lines is

permanently embroiled in

financial and archeological

challenges. The bicycle is only

for those with unusual courage.

The scooter, however is just

right.

Report courtesy of

The

Independent

|

|

|

|

![]()

![]()