|

The edition of the French daily

newspaper Le Matin, on sale on 31 January 1907, launched an unprecedented

challenge: “Is there anyone who will undertake to travel this summer from Peking

to Paris by automobile?”

Absorbed by the excitement about a

new motor vehicle race, enthusiasts came down from all over Europe, though after

looking into the journey it was evident that the rally was going to be very

difficult, and most likely impossible. The number of enrolled competitors came

down to twenty-five. However, on the morning of 10 June, right before the rally,

only five competitors showed up: two De Dion-Boutons and a Contal three-wheeler

representing France, a Dutch Spyker and the Itala of Prince Scipione Borghese,

boarded by mechanic Ettore Guizzardi and journalist Luigi Barzini.

Being an experienced traveller, a

few weeks before Borghese prepared fuel and spare parts, set on intervals for

the journey, arranging them to come by camel wherever was necessary. A large

amount of the 16,000 kilometres of the journey would pass through wastelands and

semi-desert areas, thousands of kilometres away from civilization, with no roads

to be seen nearby.

Everyday was a conquest and a new

challenge for Borghese and his crew. From the mountain mule tracks around Peking

to the desert of Gobi, then to the wavy vastness of Mongolia where Itala was

able to reach the speed of 90 kilometres an hour, beating even the horses of

Mongolian nomads. Then, after the intense heat, mud (just as insidious as

quicksands), rivers to be forded and a nagging rain that lasted for days

welcomed the open Itala into Siberia. To get a better orientation as they were

going through unfamiliar lands, the crew travelled for thousands of kilometres

following telegraph poles, the new symbols for progress. To get past the Baykal

lake, they travelled on the tracks of the Trans-Siberian Railway as if they were

a train themselves.

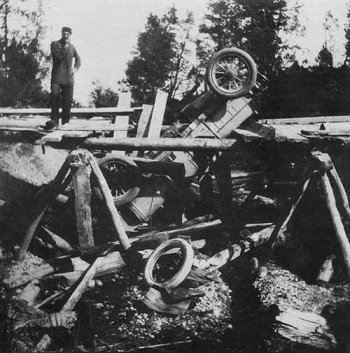

Itala continued to cover many

kilometres and proved to be unstoppable even after falling off a bridge, and its

crew members heroically withstood such journey. Once they got to Russia, as at

the point the worst was overcome, Borghese was so sure of his vehicle that he

decided to make a detour and attend a great ball dance in his honour in St.

Petersburg. Borghese knew what he was doing. On 10 August, Itala entered Paris

with victory more than twenty days before the only other contestant that was

able to reach the end.

Prince Scipione Borghese,

the driver

Born in February

1871 in the outskirts of Pisa, aristocrat Don Scipione

Borghese was 36 years old at the time of the Rally and had a

solid reputation as an alpine, a traveller and explorer.

However, he was also a senator of the Kingdom, diplomatic

and passionately fond of vehicles, those wonderful motor

vehicles that were just dawning but whose potential he was

firmly convinced of.

|

|

|

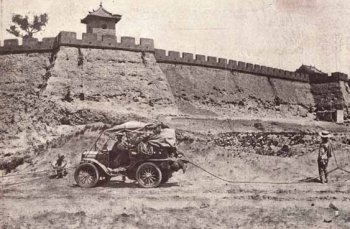

The Itala and its

intrepid crew faced a non-stop series of trials on

the 1907 journey, seen passing the Great Wall of

China (top) and surviving a crash off a bridge

(above). |

|

|

|

|

The edition of the

French daily Le Matin, on sale on 31 January 1907, launched an

unprecedented challenge: "Is there anyone who will undertake to travel this

summer from Peking to Paris by automobile?" Above: In the Gobi desert. |

|

|

As he had already began planning a pleasure trip to Peking

in that fateful year 1907, one morning the Prince read about

the strange challenge in the newspaper Le Matin and, with no

hesitation, he decided to take part in the rally using an

all-Italian vehicle which he personally prepared. He was

also going to make all the arrangements and cover all

expenses and, of course, he was going to be the one to

drive. Borghese was strongly determined to win and had all

it takes to do it. A true gentleman, resolute and cold, in

the Rome jet set he was allegedly nicknamed "The English

Officer" due to his reserved manners. Perhaps, he wasn't an

outgoing person but was nevertheless a man of character, as

he proved to be.

Ettore Guizzardi,

the mechanic

A trueborn native of Romagna in 1907, Guizzardi became the

trustworthy driver and mechanic of Prince Borghese for ten

years. His past was peculiar. When he was fifteen, while

watching his father, an engine driver, the train on which

they were travelling derailed near Borghese's castle. His

father died, but fortunately Ettore, who was urgently

brought to the castle, survived and only suffered minor

injuries - thereafter he ended up staying in the castle.

Borghese quickly became aware of his inborn attraction to

engines and made him study mechanics, working on Fiat's

workshops, at the Ansaldo plant in Genoa and in other

factories. A truly natural talent for gears, Guizzardi was a

tireless and enthusiast worker, but mainly loved Itala as if

it was his daughter. Barzini points out that one of his

favourite hobbies during the journey was to lie back under

the car and contemplate it from one side to the other, "from

bolt to bolt, part to part, and screw to screw".

Luigi Barzini,

the journalist

Luigi Barzini

was slightly younger than Borghese. He was born in Orvieto

on 7 February 1874 and he also showed up at the start of the

Rally with good credentials. A correspondent for the

Corriere della Sera first from London and then in China

during the Boxer Rebellion, he was able to develop a deep

bond with his readers, a relationship that became even

tighter during the Rally. People awaited to receive every

message holding their breath and "suffering" with him,

wondering and being astonished at the vivid descriptions of

far away countries, which at the time were unknown. Thanks

to Barzini, the Peking to Paris Rally remained memorable for

such a long time. He was the unwanted third party, as it

were, who sometimes didn't even have a seat - often he had

to snuggle on the ground and rested his feet on the

footboard so as to leave space for the luggage. His daring

attempts to track down telegraphs along the journey in order

to send his articles to the newspaper were deservedly part

of a true adventure. Barzini was a correspondent for the

Corriere della Sera as well as for the British paper The

Daily Telegraph.

|

|

|

|